Respect Privacy

How to Respect Privacy: A Constellation of Principles

By Kevin Herms

In the privacy community, respect is frequently demanded. We regularly enjoin our colleagues to foster a solemn sense of respect for privacy. In fact, the phrase "respect privacy" has acquired the status of a cliché, serving as a blunt tool to brandish whenever a privacy problem surfaces. But what exactly do we mean when we offer this admonition? How do we translate respect for privacy to concrete action?

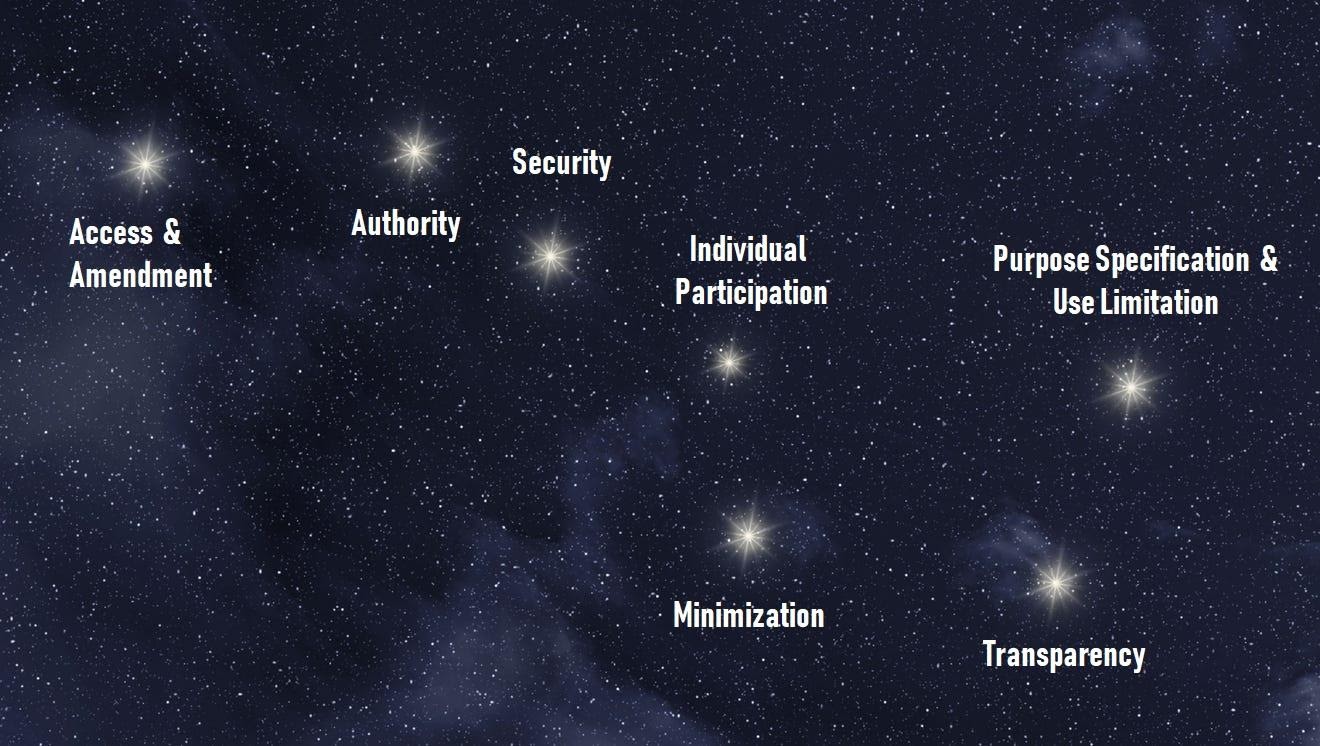

At the U.S. Department of Education, we believe that respecting privacy means building a culture that values our customers and stakeholders. It means establishing rules and procedures that foster accountability for safeguarding personal information. And we accomplish this by weaving privacy considerations into the fabric of the Department’s work. This kind of an approach is needed because privacy cannot be understood as a single idea to address at a single point – privacy is too complex and cross-cutting for that. In fact, privacy must be understood as a constellation of principles that empowers a privacy program to successfully navigate the twists and turns of the information life cycle.

What are the principles that make up this constellation? Well, they are our old friends – the Fair Information Practice Principles (FIPPs). As explained in OMB Circular A-130, the FIPPs are a collection of widely accepted principles that agencies use when evaluating information systems, processes, programs, and activities that affect privacy. The FIPPs are not requirements; rather, they are principles that agencies can apply according to their mission and programmatic needs. We think of the FIPPs as a kind of a playbook that can help privacy programs analyze and address privacy risks.

Rooted in a 1973 Federal Government report from the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare Advisory Committee, the FIPPs have informed federal law and the laws of many U.S. states and foreign nations. The precise expression of the FIPPs has varied over time and in different contexts. However, the FIPPs retain a consistent set of core principles. Circular A-130 characterizes the FIPPs as follows:

-

Access and Amendment. Agencies should provide individuals with appropriate access to personally identifiable information (PII) and appropriate opportunity to correct or amend PII.

-

Accountability. Agencies should be accountable for complying with these principles and applicable privacy requirements, and should appropriately monitor, audit, and document compliance. Agencies should also clearly define the roles and responsibilities with respect to PII for all employees and contractors, and should provide appropriate training to all employees and contractors who have access to PII.

-

Authority. Agencies should only create, collect, use, process, store, maintain, disseminate, or disclose PII if they have authority to do so, and should identify this authority in the appropriate notice.

-

Minimization. Agencies should only create, collect, use, process, store, maintain, disseminate, or disclose PII that is directly relevant and necessary to accomplish a legally authorized purpose, and should only maintain PII for as long as is necessary to accomplish the purpose.

-

Quality and Integrity. Agencies should create, collect, use, process, store, maintain, disseminate, or disclose PII with such accuracy, relevance, timeliness, and completeness as is reasonably necessary to ensure fairness to the individual.

-

Individual Participation. Agencies should involve the individual in the process of using PII and, to the extent practicable, seek individual consent for the creation, collection, use, processing, storage, maintenance, dissemination, or disclosure of PII. Agencies should also establish procedures to receive and address individuals’ privacy-related complaints and inquiries.

-

Purpose Specification and Use Limitation. Agencies should provide notice of the specific purpose for which PII is collected and should only use, process, store, maintain, disseminate, or disclose PII for a purpose that is explained in the notice and is compatible with the purpose for which the PII was collected, or that is otherwise legally authorized.

-

Security. Agencies should establish administrative, technical, and physical safeguards to protect PII commensurate with the risk and magnitude of the harm that would result from its unauthorized access, use, modification, loss, destruction, dissemination, or disclosure.

-

Transparency. Agencies should be transparent about information policies and practices with respect to PII, and should provide clear and accessible notice regarding creation, collection, use, processing, storage, maintenance, dissemination, and disclosure of PII.

At the Department of Education, we're taking steps to modernize and mature our privacy program. To do this, we're drawing our inspiration from the foundational legacy of the FIPPs. For example, we're designing new processes for our privacy impact assessments (PIAs) that will better align our risk analysis with the FIPPs framework. We're seeking to transform our PIAs into a more effective instrument for documenting and addressing privacy risks at each step of the system development process. In addition, we’re contemplating ways to better incorporate the results of our PIAs into the Department’s risk scorecards so we can quantify, track, and manage privacy risks in a more methodical manner.

To be sure, the FIPPs are only a starting point in our effort to mature the Department’s privacy program. The FIPPs are designed to function as maxims, not commandments. However, we’ve found that the nearly 50-year-old FIPPs remain fully relevant to our core mission. And we believe that any path toward a stronger, more successful privacy program begins with these nine indispensable principles.

In our voyage to respect privacy, we chart our course with the FIPPs.

Kevin Herms is the Chief Privacy Officer, the Senior Agency Official for Privacy, and the Director of the Student Privacy Policy Office at the U.S. Department of Education.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not express the views or opinions of the Federal Privacy Council.